Brain health tips and strategies

Life stage approach to brain health

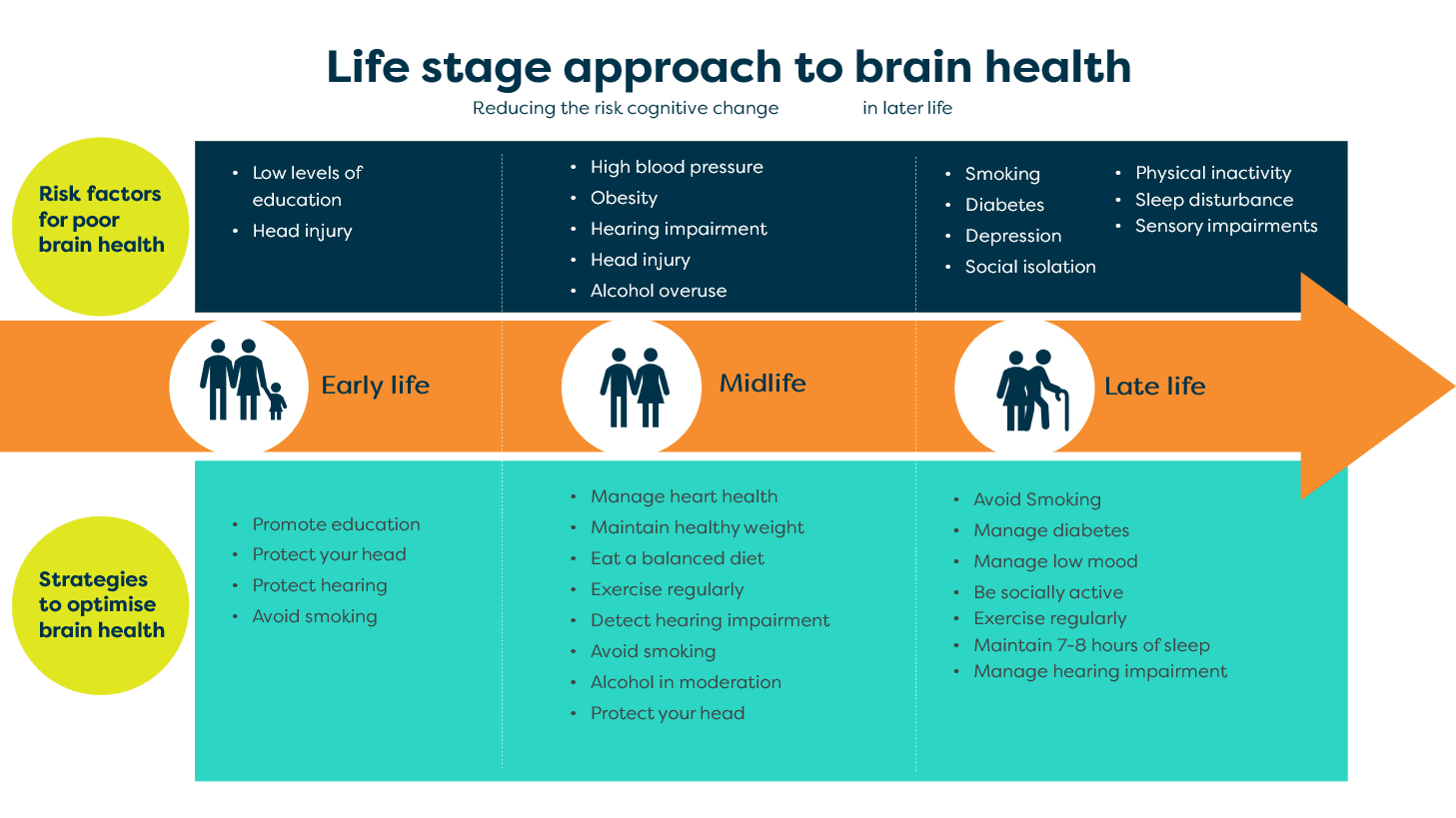

There are several risk factors linked to cognitive changes in later life. Some factors can be easily modified by incorporating simple strategies that optimise brain health.

We now know that adopting a brain-healthy lifestyle is beneficial at every stage of life. This is what we call a life-stage approach to risk reduction.

We now know that adopting a brain-healthy lifestyle is beneficial at every stage of life. This is what we call a life-stage approach to risk reduction.

By understanding the modifiable risk factors associated with poor brain health, we can make the necessary changes to maintain a healthy brain.

Where to start

The first step to optimising your brain health is to download the BrainTrack app from the app store and complete the check-in quiz. The quiz results will help you identify risk factors that may impact your brain health.

You will see where you are doing well in supporting positive brain health and learn strategies to reduce your brain health risk.

Maintain a healthy heart

Understanding the risk

Cardiovascular conditions that affect the heart and blood vessels are linked to a higher risk of cognitive decline later in life, especially in your 40s and 50s.1, 2, 3

The main conditions known to increase the risk of dementia include:

- high blood pressure (also known as hypertension)

- high cholesterol

- type 2 diabetes

- obesity

- heart disease (for example, atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure, previous heart attack)

- smoking.4

Cardiovascular conditions impact the integrity of the blood vessels that feed our brain. This can cause less oxygen and nutrients to reach our brain cells. Over time, our brain cells may shrink or die, leading to a gradual decline in cognition and everyday function.

High blood pressure, heart disease and diabetes place stress on the structure of the blood vessels, reducing blood flow to the brain. High cholesterol and obesity can cause a build-up of fatty tissue or plaque inside the blood vessels. This can block blood flow, increase blood pressure and strain the heart.

These cardiovascular conditions are easily identified and are often treatable. Diagnosis and treatment are essential for good heart health and reducing the impact on your cognitive health.5

Research shows that treating high blood pressure, especially in midlife, may reduce the risk of developing dementia later in life.6 There is also strong evidence that your risk of both heart disease and stroke, and the associated risk of dementia, drops when you stop smoking.7

Reducing the risk

Many cardiovascular conditions can be managed using simple medical and lifestyle strategies in consultation with your GP or specialists.

Strategies include:

- attending regular health checks and following the advice of your health professional (for example, your GP or specialist), especially if you have a family history of cardiovascular conditions

- treating hypertension4

- maintaining a healthy weight

- eating a healthy, well-balanced diet

- exercising regularly

- quitting smoking.

Maintain a healthy weight

Understanding the risk

Obesity and high blood pressure

Evidence suggests that a higher body mass index (BMI) is linked to an increased risk of cognitive decline.4 Obesity and high blood pressure have been identified as key dementia risk factors in midlife (45–65 years).8, 1

Obesity and diabetes

Obesity is also linked to insulin resistance or pre-diabetes, where cells in the body cannot use the hormone insulin effectively.9 Diabetes is an especially significant risk factor for developing dementia after 65.1

Diabetes and dementia

People with diabetes have a 20 per cent increased risk of developing dementia.4 This risk increases further with longer, more severe symptoms of diabetes.10 High blood glucose levels and increased inflammation associated with diabetes may also impair cognition.4

People who eat a Mediterranean diet (a diet low in meat and dairy and high in fruit, vegetables and fish) have fewer vascular risk factors. They tend to have reduced plasma glucose, serum insulin concentrations, insulin resistance and oxidative stress and inflammation markers.11

Studies have found that a weight loss of 2 kg or more in people with a BMI greater than 25 helped improve attention and memory.

The World Health Organisation recommends people with midlife weight gain and/or obesity seek interventions to reduce the risk of cognitive decline and/or dementia.11

Reducing the risk

- Eat a well-balanced diet.11

- Monitor your intake of high-fat or high-calorie foods that contribute to obesity and poor cardiovascular health.4

- Monitor and maintain your blood glucose levels within the target range.

- Limit alcohol intake to help control your weight and general health.

- Exercise regularly.

- Talk to your GP about accessing support, such as a nutritionist or exercise physiologist.

Eat a balanced and nutritious diet

Understanding the risk

A healthy diet is key to maintaining a healthy brain and body. Our brains require a range of nutrients to function well. The overconsumption of some foods can increase our chance of developing health conditions harmful to the brain and body.

Various diets have been explored in terms of their health benefits. While no specific diet is firmly associated with preventing dementia, evidence shows that healthy eating patterns are associated with better brain health,12 particularly when combined with other healthy lifestyle strategies (for example, physical activity).

Diets rich in vitamins, minerals and essential fatty acids may help to protect our brains by promoting important anti-inflammatory and antioxidant processes.

The World Health Organisation guidelines recommend a Mediterranean diet to reduce the risk of cognitive decline and/or dementia.11 The Mediterranean diet is rich in green leafy vegetables, wholegrains and ‘good’ fats (for example, olive oil, avocado and oily fish, such as salmon) and low in red meat and dairy products. This diet is associated with better performance on memory and other cognitive tests13 and reduced cardiovascular disease.14

Other foods that may reduce the risk of dementia include:

- a high intake of fruits and vegetables every day in people over 65 15

- fish and fish-derived ‘good fats’16, 17

- nuts, olive oil and coffee 18

Reducing the risk

Eat a range of healthy foods, including:

- grain foods and cereals (preferably wholegrains), for example, bread, pasta, rice, quinoa and polenta

- vegetables, legumes and beans in a variety of colours

- fruit

- dairy products (preferably low-fat options) or alternatives, such as soy-based products

- lean meats, poultry, fish, eggs, tofu, nuts and seeds to ensure adequate protein intake, particularly as you get older.

Monitor fat

- Be aware of overconsuming high-fat food.

- Include good fats that contain essential nutrients, such as olive oil, nuts, avocado and oily fish.

- Minimise unhealthy saturated fats linked with high cholesterol and cardiovascular disease. These fats are in processed or fried foods (for example, deli meats, sausages, fries, pies, doughnuts), biscuits, cakes, pastries and full-cream dairy products.

- Avoid trans-fats and hydrogenated oils in deep-fried or baked goods with a long shelf-life (for example, supermarket pastries, fries).

Watch your salt intake

- Look for hidden added salt in processed or packaged foods.

- Use salt sparingly when cooking or eating to help control your blood pressure.

- Instead of salt, try using different herbs and spices to add flavour.

Look out for hidden sugar

- Sugar is naturally found in many foods, including fruit, vegetables and dairy products. Be mindful of consuming sweet treats like lollies, chocolates, desserts and soft drinks.

- Watch for hidden sugars often added to foods like juices to preserve or enhance flavour.

- Look out for foods marketed as low-fat (for example, yoghurts, desserts and ready-to-eat meals). These foods often have a high proportion of hidden added sugar.

Drink water

- As we get older, our body’s signal for thirst becomes less noticeable. This means we need to make a habit of drinking plenty of water before we feel thirsty. Hydration helps support the function of our brain and other organs throughout the day.

- Increase your water intake by carrying a water bottle with you, adding sliced fruit to enhance the flavour, drinking herbal tea and snacking on foods high in water (for example, cucumber, celery and tomatoes).

Further information and resources

Exercise regularly

Understanding the risk

Exercise helps keep the brain healthy by:

- promoting the growth and maintenance of blood vessels delivering nutrients and oxygen to the brain

- stimulating the survival of brain cells in regions of the brain, such as the hippocampus, which is responsible for memory 19

- reducing the risk of other chronic conditions linked to poor brain health, such as high blood pressure, heart disease, diabetes and obesity

- improving balance and strength to reduce the risk of falls 20

- improving sleep and mood 21

- improving physical function 22

- helping us connect and socialise with others

- reducing mortality. 21

As a result of these benefits, people who are physically active throughout their lives, particularly through later life (for example, 65 and onwards), are less likely to develop dementia.1

But in Australia, 75 per cent of people aged 65 years and over are not sufficiently active.23 A lack of physical activity is one of the highest contributing risk factors to cognitive decline and dementia in later life.

In the USA, UK and Europe, research shows that physical inactivity is one of the highest contributing risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease (the most common type of dementia).24 This risk factor may be particularly important in later life.1

Older adults who exercise are more likely to maintain cognition than those who do not exercise. While there is no research to show that exercise prevents cognitive decline or dementia, observational studies have found an inverse relationship between exercise and the risk of dementia.25

Reducing the risk

The World Health Organisation recommends physical activity for adults with normal cognition to reduce the risk of cognitive decline.11

The current Australian guidelines 26 recommend:

- adults carry out moderate-intensity physical activity on most days, preferably every day, totalling two and a half to five hours per week 26

- older adults carry out at least 30 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity on most (at least five) days of the week. 26

Moderate-intensity physical activities will make you breathe harder and cause your heart to beat faster. You will generally be unable to finish a sentence without taking a breath.

If you cannot manage a full 30-minute session, try exercising in smaller instalments throughout the day.

It is important to include a variety of physical activities that target different physical characteristics, including aerobic fitness, strength, balance and flexibility. Variety also helps work different muscle groups and joints throughout our bodies.

Tips to increase physical activity

- When tidying up, put things away in multiple smaller trips rather than in one big haul.

- Try to take the stairs instead of the lift whenever you can.

- During your favourite TV show, get up and move around during every commercial break.

- When you take the bus or train, get off one stop earlier and walk the rest of the way.

- If you drive short distances, consider walking instead, or park a little further away and walk the rest of the way.

- If you plan to meet a friend for coffee, why not walk together first and then head to the cafe.

The key to increasing physical activity is to find activities you enjoy. You are more likely to maintain activity if you are having fun. For example, you could learn to dance, go swimming or sign up for a yoga class. Find activities you can do with a friend or join a local walking group. This can be a great way to both meet new people and increase your physical activity.

Even people with complicated health problems can find safe ways to increase their physical activity. Start small and gradually increase the duration, frequency and intensity over time.

If you have a serious health condition or have been inactive for a long time, consult your GP or appropriate health practitioner (such as an exercise physiologist) first to make sure the activities you choose are safe.

Further information and resources

Limit your alcohol

Understanding the risk

Excessive alcohol use contributes to significant disability and mortality globally.11 Strong evidence also links excessive alcohol as a risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia.11, 27, 28, 29

A large cohort study reported a strong relationship between younger onset dementia and alcohol use disorders.30

The World Health Organisation recommends adults with normal cognition or mild cognitive impairment seek interventions to reduce or cease hazardous and harmful drinking. This will help reduce the risk of cognitive decline and/or dementia.11

Reducing the risk

The Australian guidelines for alcohol intake31 recommends:

- no more than ten standard drinks per week

- no more than four standard drinks in any one day

- at least two alcohol-free days per week.

Talk to your GP if you are drinking more than the recommended guidelines. Primary care screening, intervention and support can help reduce the risks associated with alcohol consumption.

Remember, you do not have to avoid alcohol entirely. For many people, alcohol is an important part of social activities, celebrations and cultural events. Focus on moderating your alcohol intake and drinking responsibly instead.

Further information and resources

Avoid smoking

Understanding the risk

Smoking affects both the heart and brain, increasing the risk of heart disease, stroke, cancer and developing dementia.32 There is no safe level of smoking.

The link between smoking and poor brain health is likely associated with cardiovascular risks. Neurotoxins in tobacco products increase this risk.4, 33

Reducing the risk

Stop smoking - it’s never too late! There are many resources to help you quit. Get started today by calling Quitline on 13 78 48.

Further information and resources

Optimise hearing

Understanding the risk

Research has found there may be a link between hearing loss and the risk of developing cognitive problems later in life. Early diagnosis and intervention can help improve your quality of life and reduce your risk of dementia.

Recent guidelines for dementia prevention highlight hearing loss as an important and perhaps underestimated risk factor for dementia, both in mid and later life.1 This is based on research showing a two-fold increase in the risk of developing dementia in people with mild symptoms of hearing loss compared to those with normal hearing. People with severe hearing loss may be five times more likely to develop dementia in later life.34

Researchers still do not know exactly how hearing loss and dementia are linked. But there are several possible explanations for why hearing problems may increase the risk of developing dementia.1, 34

- Hearing loss may cause some people to withdraw from conversations and participate in fewer social activities. This can reduce the amount of mental stimulation and social contact they have, both of which are important for brain health.

- Reduced hearing ability may put greater strain on the brain, as other mental resources are required to perceive, decode and process sounds. Over time, this could potentially increase the brain’s vulnerability or accelerate other underlying diseases or damage.35

- It may be that hearing loss does not actually cause dementia, but that similar processes occurring in the same person lead to both conditions. Examples include the process of aging or changes to small blood vessels that feed both the brain and our hearing organs.

It is important to understand that hearing loss is a risk factor, not a guarantee. Not everyone with hearing loss will develop dementia.25

Reducing the risk

You can protect your hearing in midlife by wearing protective equipment to reduce exposure to excessive noise. This includes industrial noise and loud music.4

There are many common signs of hearing loss. For example:

- you may be having trouble engaging in conversations with friends and family

- you have to ask people to repeat what they’ve said

- you find noisy environments more challenging

- you need to turn the television or radio up louder than usual.

If you notice problems with your hearing at any stage of life, you should talk to your GP.

Your GP may refer you for a comprehensive assessment with a hearing specialist (for example, an audiologist). This specialist will help determine any changes in your hearing and discusses management options. You may be eligible for subsidised hearing services from the Australian Government (hearingservices.gov.au) or through your private health insurance.

Research has found the use of hearing aids is protective, helping reduce the risk of cognitive decline.4

Vision

Some studies suggest an association between vision impairment and dementia in later life. This is particularly relevant for people who do not seek adequate management of their poor vision. 36

Vision changes are common as we get older. It is important to have regular examinations to check on the health of your eyes. For adults 65 years and over, Medicare subsidises one eye examination per year. If you have reduced vision, wear your glasses or contact lenses as required to avoid placing unnecessary strain on your eyes and brain.

If you or someone close to you notices any changes in your vision, talk to your GP. Early diagnosis and intervention are key to improving your quality of life and reducing your risk of dementia.

Further information and resources

Optimise your mood

Understanding the risk

A history of depression is a risk factor for developing dementia in later life. Depression is associated with reduced memory, speed of thinking and decision-making skills.

Depression is a serious condition, and there are medical specialists who can help.1

What is depression?

Everyone experiences temporary changes in mood that do not significantly affect our functioning.

But some people can experience more severe or persistent symptoms of feeling low or no longer enjoying their usual activities. This can interfere with their work, community, family or social activities.

These symptoms may be signs of depression.

The national organisation Beyond Blue reports that around 10 to 15 per cent of older Australians experience depression, with an even higher rate of around 30 per cent in older people living in residential aged care facilities . 37

Symptoms of depression can include:

- emotional changes, such as sadness, low mood, worry or feeling anxious

- behavioural changes, such as withdrawing from social activities, irritability or increased use of alcohol (especially in men)

- physical changes, such as headaches or gastrointestinal upset

- unhelpful thinking patterns, such as ‘I’m worthless’ or ‘life is not worth living’.

Depression can be difficult to identify and diagnose in older people. Older people generally experience less of the classic depression symptoms like sadness and lack of enjoyment. Instead, they display more physical and behavioural symptoms, such as difficulty sleeping, fatigue, dizziness, appetite changes, irritability, forgetfulness and poor concentration. Many people experience both depression and anxiety, which can further complicate diagnosis.

Even after diagnosis, depression can be difficult to treat in older people and can persist for long periods.38 For approximately - two-thirds of older people with depression, it can take around 18 months to recover. There is also a greater risk of depression recurring in the future.

It is important to note that middle-aged and older men are one of the highest-risk groups for suicide. Depression is a key contributing factor to this, along with poor physical health and reduced social support.39

What causes depression?

Depression can be due to multiple factors, including:

- life stressors (for example, family conflict or bereavement)

- a family history of depression

- personality

- previous life experiences (for example, poor coping skills in difficult or traumatic circumstances)

- anxiety and stress

- drug and alcohol use

- physical illness

- stroke and vascular risk factors, such as heart disease

- changes in chemicals (neurotransmitters) in the brain.

In older people particularly, life stressors like retirement, social isolation and moving into residential care can be strong risk factors for depression. A person who has previously experienced depression or who has previously attempted suicide is at very high risk.

What is the link between depression and dementia?

As many as 75 per cent of older people with depression will experience mild cognitive impairment. This particularly affects aspects of memory, thinking speed and higher-level executive functions, such as planning, problem-solving, multi-tasking and organisational skills.40 This cognitive impairment can persist even when depressive symptoms have subsided, possibly due to underlying structural changes in the brain.41

Longer-term research studies reveal links between depressive episodes in later life and the risk of developing dementia.42 The odds of developing dementia were 85 per cent higher in people with late-life depression, particularly in relation to vascular dementia.43

However, the relationship between depression and dementia is complex. In some cases, depression may occur in older people as a symptom of dementia rather than the other way around. The link between depression and dementia likely relates to several factors.44, 45 These include:

- changes in the brain’s structure, leading to cell death. This is common in areas such as the hippocampus, important for memory functioning, and the basal ganglia, important for speed of thinking and emotion regulation

- damage to the blood vessels feeding the brain (often associated with heart and vascular disease) leading to white matter changes, which affects blood flow to critical brain regions

- changes in chemical signalling in the brain (i.e., neurotransmitters like serotonin)

- a possible increased build-up of beta-amyloid in the brain, the same sticky protein associated with Alzheimer’s disease.46

Reducing the risk

Remember, depression is a serious health condition and does not represent a weakness in character. Thinking of depression in this way contributes to ongoing stigma and shame around depression and may prevent people from seeking help to manage their symptoms.

Because of its impact on our general wellbeing and the potential impact on our brain health, you should look out for signs of depression in yourself and your loved ones.

Fortunately, there are many effective medicated and non-medicated treatments for depression. The goal of treatment should go beyond improving symptoms. Maximising brain and cognitive health is also important, particularly for older people.

In Australia, many treatments are available under Medicare. However, you will need a referral from your doctor and possibly a Mental Health Plan to access these rebates.

When seeking help to manage depression (or related symptoms such as stress and anxiety), you should start by speaking with your GP. They can help you find an approach that works, whether drug-based, non-drug-based or a combination of the two.

Drug-based approaches involve taking medications, such as anti-depressants, mood stabilisers or even anti-anxiety drugs. Each of these medications works in a slightly different way and may have different side effects. Newer antidepressant drugs are very safe and may even have added protective effects for brain structures like the hippocampus, which is critical for memory functioning.

Your doctor can work with you to determine which medication, if any, is appropriate for you. These drugs typically take a few weeks to work as they build up f neurotransmitters levels in the brain.

Many people remain on these drugs after their initial symptoms improve to reduce the risk of depression recurring in future.

Non-drug treatments like psychological or talking therapies usually involve seeing a specialist, such as a clinical psychologist, for several sessions.

There are various approaches, including Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, which focuses on identifying and changing unhelpful or unhealthy patterns of thinking, feeling and behaving. Other non-drug approaches include Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Problem-Solving Therapy.47

Cognitive training programs may help people experiencing significant effects on their thinking skills and day-to-day functioning.

These training programs are considered safe and effective. Work with a qualified mental health professional to ensure that your treatment considers your specific symptoms and circumstances.

Further information and resources

Optimise your sleep

Understanding the risk

Why do we need to sleep?

Sleep is a crucial part of our behaviour. In fact, we spend a third of our lives sleeping. While we do not fully understand its exact function, we do know that sleep plays a major role in brain health. It is critical for alertness, mood, daytime functioning and cognition.

Research shows that various physical processes occur during different stages of our sleep cycle. These processes are likely essential for forming and strengthening new memories.48

Sleep is also thought to be important for a process called neurogenesis. Neurogenesis is the formation of new nerve cells in the brain, including the hippocampus, critical for memory functioning.49

New research also shows that deeper stages of sleep may clear toxins and harmful proteins associated with some types of dementia from the brain.

While some changes to sleep may be part of the normal ageing process, they can still impact our alertness, mood and thinking. There is increasing evidence linking sleep disturbance with our risk of developing depression, cognitive problems and dementia later in life.50, 51

This seems particularly relevant in people who have already experienced depression, where sleep problems are linked with cognitive decline and altered brain functioning.52, 53

In people with sleep apnoea, sleep is not only disrupted by frequent awakenings. The brain is also starved of oxygen, which is linked to brain shrinkage and memory problems.54

The precise relationship between sleep problems and dementia (including which one comes first) is still uncertain. Research suggests that sleep duration, sleep quality and sleep apnoea all seem to be related to an increased risk of dementia later in life.55, 56

Reducing the risk

The amount of sleep we need varies from person to person. Adults should generally aim for between seven and nine hours a night. However, research shows that our sleep patterns change as we get older, and we may need less sleep.57

From your mid-40s, it is common for people to have difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep through the night.58

The structure of our sleep is also known to change with age. Older people tend to spend more time in the lighter stages of the sleep cycle and less time in the deep and dreaming phases of sleep. This means it may not be the duration but the quality of sleep that matters.

What can I do if I am having trouble sleeping?

It is important to seek help if:

- you are having trouble falling or staying asleep

- you snore

- you are excessively sleepy during the day

- you seem to be acting out your dreams in your sleep

- your sleep is impacting your bedtime partner or your daily functioning.

Start by talking to your GP. They will discuss common causes of sleep problems and may refer you for an overnight sleep study. Managing your sleep problems will depend on the causing factors. For example, medical conditions, depression, anxiety, substance and medication use, daily sleep habits and breathing problems are all common causes of sleep disturbance but have different treatments.

General tips for healthy sleep:

- Establish a regular sleep schedule. Getting up at the same time every day helps to keep your body clock regular and establishes a healthy sleep-wake routine. Only go to bed when you feel sleepy. When you wake up, get plenty of sunlight exposure to help maintain your body rhythm.

- Create a relaxing bedtime routine. Having a good bedtime routine helps to tell your brain and body that it is time for sleep. Before bed, dim the lights, read a book or do light stretches to help wind down. Avoid using technology, consuming caffeine or alcohol, exercising heavily, eating heavy meals or taking hot showers or baths too close to bedtime.

- Maintain a good sleep environment. Your bed, sheets and pillow should be comfortable and not too hot or cold. Your bedroom should be a relaxing place without distractions like a TV, radio or phone.

- Be smart about napping. While naps can help you recharge during the day, try to keep them to 30 minutes maximum. Schedule them for the early afternoon so they do not affect the duration and quality of your sleep at night.

- Keep physically active. Physical activity helps you regulate your body clock and fall asleep. It also increases deep sleep and reduces night waking. However, try not to exercise close to bedtime as it can be too physically stimulating. Exercise is most effective for your sleep when done in the morning or early afternoon.

- Do not force sleep. If you cannot sleep after 20 to 30 minutes of lying-in bed, get up and move to another area of the house. Sit quietly with no TV, computer, lights or snacks, and return to bed when you start to feel tired again. Try not to watch the clock. This can cause you to feel anxious or upset and could make your sleep problems worse!

- Do not use sleeping medications as a long-term solution. The use of sedative-hypnotics and the benzodiazepine class of drugs should be for no longer than two weeks. These medications do not fix sleep problems and are associated with increased confusion and falls in older people. Psychological strategies appear to be effective for some types of sleep problems.

- Continuous positive airway pressure is effective for people with sleep apnoea.

- Speak to your GP about the use of melatonin if you have difficulty falling asleep at night.

Further information and resources

Connect with people

Understanding the risk

Social interactions help give us a sense of belonging and connection with the world around us. This can improve our wellbeing and reduce feelings of loneliness or depression. Social activities can also increase our cognitive reserve and reduce our risk of cognitive decline.59

Social isolation is linked to a number of conditions, including dementia, hypertension,60 coronary heart disease 61, 62, 63 and depression 64 Social isolation can also reduce cognitive activity, which is linked to a faster rate of cognitive decline and low mood.65

Reducing the risk

It is especially important to be aware of social engagement as we get older. This is a time when we may face changes that impact our opportunities to socialise.

These may include:

- retirement

- moving house

- personal losses (for example, the death of a family member or close friends)

- driving less or not at all.

It is important to find ways to be regularly social in a way that interests you, that you feel comfortable with, and that you enjoy.

This could involve:

- catching up with friends or family over the phone or in-person

- joining a group activity through your local council, art gallery or museum

- joining activities through organisations like the Men’s Shed Association or Volunteering Australia

- joining an exercise or sports club

- having friendly chats with shopkeepers or people you encounter throughout the day.

Protect your head

Understanding the risk

The soft tissue of the brain is housed inside a bony skull. Despite this layer of protection, the brain is still vulnerable to damage if we injure our heads.

Head injuries typically result from an impact to the head. This may be caused by a fall, car accident, sporting injury or assault. They can also result from non-impact events like whiplash. Head injuries can range from very minor, with no effects on the brain, to very severe or even life-threatening.

Research has shown that moderate to severe head injuries (when a person loses consciousness for more than one hour) may increase the risk of developing dementia later in life.1, 66, 67

Chronic, repeated blows to the head, such as those experienced in military combat or by contact athletes, may also increase the risk of developing dementia later in life. Repetitive mild brain injury is associated with chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which can result in dementia.68

This does not mean that you will definitely develop dementia if you have had a moderate, severe or repeated traumatic head injury. It simply means you may be at greater risk. This may be due to a number of factors following a head injury, such as a loss of brain tissue, damage to the blood vessels feeding the brain 69 or an increase in particular proteins in the brain that are associated with dementia.70

Reducing the risk

The best approach is to protect your head and avoid injury in the first place. You can do this by:

- wearing a helmet and appropriate safety gear during sporting or recreational activities, including riding bicycles, scooters or motorbikes

- wearing a seatbelt while travelling in any motor vehicle, as a driver or passenger

- obeying road rules and refraining from using drugs or alcohol when driving or riding in a vehicle (including cars, bicycles and motorbikes)

- taking extra care or asking for help on slippery surfaces, stairs and ladders

- addressing factors that pose a risk for slipping and falling, such as installing and using handrails around stairs or in your bathroom

- securing rugs, carpets and loose electrical cords to reduce your chance of tripping

- using a walker or cane if you feel unsteady on your feet

- watching for pets or young children who might get under your feet while walking.

Further information and resources

Set brain healthy goals

Creating and maintaining healthy habits

Brain-healthy strategies can be introduced across many aspects of our lives, including the activities we do, the foods we eat and how we think about our health. These strategies can make a difference at any age.

But sometimes, putting these lifestyle changes into action can be difficult. If you have trouble changing your behaviour or sticking with changes over time, you are not alone.71 With encouragement and support, you can make and maintain changes and see benefits over time.72

There are several tips to help you make and maintain changes that can help improve your general health and wellbeing and reduce your risk of dementia.

Set goals. Changes are easier to make when they are related to a specific goal. For example, you might like to be more physically active, reduce your alcohol consumption or increase your participation in social activities. It is okay to have more than one goal and change your goals over time.

The important thing is to spend time setting your goals and planning how you will achieve them. A well-formed goal should be SMART:

- Specific: What exactly do I want to accomplish?

- Measurable: How will I know when I have accomplished it? What markers of progress will I look for along the way?

- Achievable: What do I need to do to meet this goal? Is this within my reach?

- Realistic: Do I have access to the resources I will need?

- Timely: When exactly do I expect to achieve this goal?

Start simple. Do not expect to change your life in one day. Many people start with a high level of motivation and commit to a level of change that is not realistic or sustainable. Try to make gradual changes, working consistently on each step of your goal until it becomes comfortable and part of your routine. Then you can work on increasing the amount, frequency or intensity of the activity.

Build on what you know. Changing habits is often easier when you integrate the new habit into a pre-existing routine or habit. For example, if your aim is to increase your daily fruit intake, you could start by adding chopped fruit to your regular breakfast.

Enlist help. Tell your friends and family about your goals. They can help provide encouragement and motivation. Better yet, involve a friend or family member to make yourself accountable to someone else. This will increase your likelihood of success. For example, if your goal is to walk twice a week, plan to meet a friend at a specific time and place.

Choose something you enjoy. Doing something you do not enjoy will feel like a chore and you will be less likely to stick with your new habit. Working with your interests will increase your motivation and make your goal more achievable. For example, if your goal is to increase your participation in social activities, contact your local council to see if there is a class you can join (for example, dance, art or meditation). This will allow you to socialise while also doing an enjoyable activity.

Track your progress. Tracking your progress can help keep you motivated. Try do not to get upset if you are not progressing as quickly as you would like. This may indicate that you need to adjust your approach or revisit your overall goal. It is okay to scale it back and work more gradually.

Build-in rewards. Humans respond well to rewards. There is even a specific region in the brain, known as the nucleus accumbens, devoted to processing motivation and reward. Building in incentives will help keep you motivated toward your goal. It might be something small, like a cup of tea or a piece of dark chocolate as a treat. Or it might be something bigger, like buying a new gadget or piece of clothing to celebrate reaching a progress milestone.

Further information and resources

References

- Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention and care. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2673-734.

- Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Brayne C. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: An analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(8):788-94.

- Stefanidis KB, Askew CD, Greaves K, Summers MJ. The effect of non-stroke cardiovascular disease states on risk for cognitive decline and dementia: A systematic and meta-analytic review. Neuropsychol Rev. 2018;28(1):1-15

- Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413-446. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6

- Li J, Wang YJ, Zhang M, Xu ZQ, Gao CY, Fang CQ, et al. Vascular risk factors promote conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2011;76(17):1485-91

- Gottesman RF, Schneider ALC, Albert M, Alonso A, Bandeen-Roche K, Coker L, et al. Midlife hypertension and 20-year cognitive change: The atherosclerosis risk in communities neurocognitive study. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(10):1218-27.

- Athyros VG, Katsiki N, Doumas M, Karagiannis A, Mikhailidis DP. Effect of tobacco smoking and smoking cessation on plasma lipoproteins and associated major cardiovascular risk factors: A narrative review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29(10):1263-74.

- Albanese E, Launer LJ, Egger M, Prince MJ, Giannakopoulos P, Wolters FJ, Egan K. Body mass index in midlife and dementia: Systematic review and meta-regression analysis of 589,649 men and women followed in longitudinal studies. Alz Dement. 2017; 8:165-178.

- Veronese N, Facchini S, Stubbs B, et al. Weight loss is associated with improvements in cognitive function among overweight and obese people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2017; 72: 87–94

- Chatterjee S, Peters SA, Woodward M, et al. Type 2 diabetes as a risk factor for dementia in women compared with men: a pooled analysis of 2·3 million people comprising more than 100,000 cases of dementia. Diabetes Care 2016; 39: 300–07

- WHO. Risk reduction of cognitive decline and dementia: WHO guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2019.

- Chen X, Maguire B, Brodaty H, O'Leary F. Dietary patterns and cognitive health in older adults: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;67(2):583-619.

- Radd-Vagenas S, Duffy SL, Naismith SL, Brew BJ, Flood VM, Fiatarone Singh MA. Effect of the Mediterranean diet on cognition and brain morphology and function: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;107(3):389-404

- Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvado J, Covas MI, Corella D, Aros F, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(25):e43.

- Lee ATC, Richards M, Chan WC, Chiu HFK, Lee RSY, Lam LCW. Lower risk of incident dementia among Chinese older adults having three servings of vegetables and two servings of fruits a day. Age Ageing 2017;46(5):773-9.

- Samieri C, Morris MC, Bennett DA, Berr C, Amouyel P, Dartigues JF et al. Fish intake, genetic predisposition to alzheimer disease, and decline in global cognition and memory in 5 cohorts of older persons. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2018;187(5):933–940. doi:10.1093/aje/kwx330

- Zhang Y, Chen J, Qiu J, Li Y, Wang J, Jiao J. Intakes of fish and polyunsaturated fatty acids and mild-to-severe cognitive impairment risks: a dose-response meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2016;103(2):330–340. doi:10.3945/ajcn.115.124081.

- Solfrizzi V, Agosti P, Lozupone M, Custodero C, Schilardi A, Valiani V et al. Nutritional intervention as a preventive approach for cognitive-related outcomes in cognitively healthy older adults: a systematic review. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. (Preprint)2018;1–26.

- Erickson KI, Voss MW, Prakash RS, Basak C, Szabo A, Chaddock L, et al. Exercise training increases the size of the hippocampus and improves memory. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(7):3017-22

- de Labra C, Guimaraes-Pinheiro C, Maseda A, Lorenzo T, Millán-Calenti JC. Effects of physical exercise interventions in frail older adults: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Geriatr 2015; 15: 154.

- Blake H, Mo P, Malik S, Thomas S. How effective are physical activity interventions for alleviating depressive symptoms in older people? A systematic review. Clin Rehabil 2009; 23: 873–87

- Almeida OP, Khan KM, Hankey GJ, Yeap BB, Golledge J, Flicker L. 150 minutes of vigorous physical activity per week predicts survival and successful ageing: a population-based 11-year longitudinal study of 12 201 older Australian men. Br J Sports Med 2014; 48: 220–25.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s health 2018 (Australia’s Health Series Number 16). Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2018;16 Retrieved from: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/7c42913d-295f-4bc9-9c24-4e44eff4a04a/aihw-aus-221.pdf.aspx?inline=true Accessed May, 2022.

- Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Brayne C. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: An analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(8):788-94.

- Mowszowski L, Naismith S. Your Brain Matters: A life-stage approach to dementia risk reduction. A document prepared for Dementia Australia. 2019.

- Australian Government. Department of health. Health Physical activity and exercise. Physical activity and exercise guidelines for all Australians. Australian Government. 2021. https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/physical-activity-and-exercise/physical-activity-and-exercise-guidelines-for-all-australians/for-adults-18-to-64-years Accessed May, 2022.

- Langballe EM, Ask H, Holmen J, Stordal E, Saltvedt I, Selbaek G et al. Alcohol consumption and risk of dementia up to 27 years later in a large, population-based sample: the HUNT study, Norway. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2015;30(9):1049– 1056. doi:10.1007/s10654-015-0029-2

- Sachdeva A, Chandra M, Choudhary M, Dayal P, Anand KS. Alcohol-related dementia and neurocognitive impairment: a review study. International Journal of High Risk Behaviors & Addiction. 2015;5(3):e27976. doi:10.5812/ijhrba.27976.

- Zhou S, Zhou R, Zhong T, Li R, Tan J, Zhou H. Association of smoking and alcohol drinking with dementia risk among elderly men in China. Current Alzheimer Research. 2014;11(9):899–907.

- Schwarzinger M, Pollock BG, Hasan OSM, et al. Contribution of alcohol use disorders to the burden of dementia in France 2008–13: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2018; 3: e124–32.

- National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) 2021, Health advice/ alcohol, https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/health-advice/alcohol#download Accessed March 2021.

- Zhong G, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Guo JJ, Zhao Y. Smoking is associated with an increased risk of dementia: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies with investigation of potential effect modifiers. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0118333.

- Debanne SM, Bielefeld RA, Cheruvu VK, Fritsch T, Rowland DY. Alzheimer’s disease and smoking: bias in cohort studies. J Alzheimers Dis 2007; 11: 313–21.

- Lin FR, Metter EJ, O’Brien RJ, Resnick SM, Zonderman AB, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss and incident dementia. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(2):214-20.

- Panza F, Lozupone M, Sardone R, Battista P, Piccininni M, Dibello V, La Montagna M, Stallone R, Venezia P, Liguori A, Giannelli G, Bellomo A, Greco A, Daniele A, Seripa D, Quaranta N, Logroscino G. Sensorial frailty: age-related hearing loss and the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in later life. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2018 Nov 9;10:2040622318811000. doi: 10.1177/2040622318811000. PMID: 31452865; PMCID: PMC6700845.

- Rogers MAM, Langa KM. Untreated poor vision: A contributing factor to late-life dementia. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171(6):728-35.

- Haralambous, B., X. Lin, B. Dow, C. Jones, J. Tinney and C. Bryant. Depression in older age: A scoping study. National Ageing Research Institute (NARI) funded by Beyond Blue. 2009.

- Hickie IB, Naismith SL, Norrie LM, Scott EM. Managing depression across the life cycle: New strategies for clinicians and their patients. Intern Med J. 2009;39(11):720-7.

- Conwell Y, Van Orden K, Caine ED. Suicide in older adults. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2011;34(2):451-68

- Jayaweera HK, Hickie IB, Duffy SL, Hermens DF, Mowszowski L, Diamond K, et al. Mild cognitive impairment subtypes in older people with depressive symptoms: Relationship with clinical variables and hippocampal change. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2015;28(3):174-83.

- Bhalla RK, Butters MA, Mulsant BH, Begley AE, Zmuda MD, Schoderbek B, et al. Persistence of neuropsychologic deficits in the remitted state of late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(5):419-27.

- Dotson VM, Beydoun MA, Zonderman AB. Recurrent depressive symptoms and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 2010; 75: 27–34.

- Diniz BS, Butters MA, Albert SM, Dew MA, Reynolds CF. Late-life depression and risk of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based cohort studies. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(5):326-35.

- Naismith SL, Norrie LM, Mowszowski L, Hickie IB. The neurobiology of depression in later-life: Clinical, neuropsychological, neuroimaging and pathophysiological features. Prog Neurobiol 2012;98(1):99- 143.

- Butters MA, Young JB, Lopez O, Ainzenstein HJ, Mulsant BH, Reynolds CF, et al. Pathways linking latelife depression to persistent cognitive impairment and dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2008;10(3):345-57

- Harrington KD, Gould E, Lim YY, Ames D, Pietzrak RH, Rembach A, et al. Amyloid burden and incident depressive symptoms in cognitively normal older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2017;32(4):455-63

- Arean P, Hegel M, Vannoy S, Fan MY, Unuzter J. Effectiveness of problem-solving therapy for older, primary care patients with depression: Results from the IMPACT project. Gerontologist. 2008;48(3):311-23.

- Diekelmann S, Born J. The memory function of sleep. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11(2):114-26

- Mueller AD, Meerlo P, McGinty D, Mistlberger RE. Sleep and adult neurogenesis: Implication for cognition and mood. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2015;25:151-81.

- Cho HJ, Lavretsky H, Olmstead R, Levin MJ, Oxman MN, Irwin MR. Sleep disturbance and depression recurrence in community-dwelling older adults: A prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):1543-50

- Musiek ES, Holtzman DM. Mechanisms linking circadian clocks, sleep, and neurodegeneration. Science. 2016;354(6315):1004-8.

- Naismith SL, Rogers NL, Lewis SJ, Terpening Z, Ip T, Diamond K, Norrie L, Hickie IB. Sleep disturbance relates to neuropsychological functioning in late-life depression. J Affect Disord. 2011;132(1-2):139- 45.

- McKinnon AC, Hickie IB, Scott J, Duffy SL, Norrie L, Terpening Z, et al. Current sleep disturbance in older people with a lifetime history of depression is associated with increased connectivity in the Default Mode Network. J Affect Disord. 2018;229:85-94.

- Cross NE, Memarian N, Duffy SL, Pagoula C, LaMonica H, D’Rozario A, et al. Structural brain correlates of obstructive sleep apnoea in older adults at risk for dementia. Eur Respir J. 2018;52(1):1800740.

- Leng Y, McEvoy CT, Allen IE, Yaffe K. Association of sleep-disordered breathing with cognitive function and risk of cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(10):1237–45. Liang Y, Qu LB, Liu H. Non-linear associations between sleep duration and the risks of mild cognitive impairment/dementia and cognitive decline: A dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018; Jul 23:[Epub ahead of print].

- Shi L, Chen SJ, Ma MY, Bao YP, Han Y, Wang YM, et al. Sleep disturbances increase the risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;(40):4-16.

- Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, Alessi C, Bruni O, DonCarlos L, et al. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: Methodology and results summary. Sleep Health. 2015;1(1):40-3.

- Mander BA, Winer JR, Walker MP. Sleep and human aging. Neuron. 2017;94(1):19-36.

- James BD, Wilson RS, Barnes LL, Bennett DA. Late-life social activity and cognitive decline in old age. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2011;17(6):998-1005.

- Yang YC, Boen C, Gerken K, Li T, Schorpp K, Harris KM. Social relationships and physiological determinants of longevity across the human life span. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016; 113: 578–83

- Hemingway H, Marmot M. Evidence based cardiology: psychosocial factors in the aetiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease. Systematic review of prospective cohort studies. BMJ 1999; 318: 1460–67

- Pantell M, Rehkopf D, Jutte D, Syme SL, Balmes J, Adler N. Social isolation: A predictor of mortality comparable to traditional clinical risk factors. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(11):2056-62.

- Floud S, Balkwill A, Canoy D, Reeves GK, Green J, Beral V, et al. Social participation and coronary heart disease risk in a large prospective study of UK women. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2016;23(9):995-1002.

- Santini ZI, Koyanagi A, Tyrovolas S, Mason C, Haro JM. The association between social relationships and depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 2015; 175: 53–65.

- Kuiper JS, Zuidersma M, Oude Voshaar RC, et al. Social relationships and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Res Rev 2015; 22: 39–57.

- Wang HK, Lin SH, Sung PS, Wu MH, Hung KW, Wang LC, et al. Population based study on patients with traumatic brain injury suggests increased risk of dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(11):1080-5.

- Perry DC, Sturm VE, Peterson MJ, et al. Association of traumatic brain injury with subsequent neurological and psychiatric disease: a meta-analysis. J Neurosurg 2016; 124: 511–26.

- McKee AC, Stern RA, Nowinski CJ, et al. The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain 2013; 136: 43–64.

- Franzblau M, Gonzales-Portillo C, Gonzales-Portillo GS, Diamandis T, Borlongan MC, Tajiri N, et al. Vascular damage: A persisting pathology common to Alzheimer’s disease and traumatic brain injury. Med Hypotheses. 2013;81(5):842-5.

- Johnson VE, Stewart W, Smith DH. Traumatic brain injury and amyloid-β pathology: A link to Alzheimer’s disease? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11(5):361-70.

- Marteau, T.M., D.P. French, S.J. Griffin, A.T. Prevost, et al., Effects of communicating DNA-based disease risk estimates on risk-reducing behaviours. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews, 2010(10): p. CD007275.

- Gardner, B., P. Lally, and J. Wardle, Making health habitual: The psychology of “habit-formation” and general practice. The British Journal of General Practice, 2012. 62(605): p. 664–666.